Health and Well-being - Part 10.1 - Differences That Make A Difference

"There is so much talk about the system. And so little understanding." - Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

[NB: The Health and Well-being series of articles are reworked and updated from a similar series that first appeared on The Stoic Agilist. My goal for this series of articles is to serve as an example of how anyone might go about improving and sustaining their health and well-being. The effort to sort out what is known about metabolic diseases and how that fits within an overall health strategy has been a deep dive indeed. So much so that it needs to be split into several parts.]

For years I worked to impress upon management the importance of thinking about software development in terms of systems. Leveraging the excellent work of Lyneis and Ford1, I developed a simple model for evaluating and monitoring the health of the entire software development ecosystem. (The details of this model are described in my “Systems Thinking, Project Management, and Agile“ series of articles.) With very few exceptions, management either wasn’t interested or couldn’t grasp even the simple concepts.

The development teams, however, were enthusiastic about the picture presented by the model but regretted that, in their view, they had no ability to impact the overall system. This, of course, wasn’t true and my efforts to teach them how they can impact the larger system also proved difficult. Again, with very few exceptions, most developers just wanted to work on what interested them and expected someone else to “fix the system.” Complaining about things they don’t want to influence (but can) is a common developer character trait. It’s soothing to them. Much like a toddler who sucks his thumb while clutching his teddy bear.

Most scrum masters and a majority of Agile coaches I’ve worked with were pretty much clueless of this model and were too busy playing whack-a-mole and fighting fires when things didn’t go according to the book. The book being whatever flavor of Agile they learned in a two day workshop. Maybe they had something a little more comprehensive like SAFe. The few that were dialed into elements of the model I used couldn’t explain in clear terms how it was they were able to intuitively identify where the sources of agony were on scrum teams or within organizations. It was fun, and reassuring, for me to listen to them describe in convoluted detail how they went about solving systemic challenges while I followed along with the relatively simple model in my head.

Not part of this model were other tools I developed to make the model even more effective. Many of these tools are derived from behavioral psychology and neuroscience. Leveraging my undergraduate degrees, I often found it helpful to think about technical teams and the development process in terms of biomechanics. We are, after all, dealing with human animal activity. Most notable, I knew where energy needed to be put into the system, which parts of the system were energy drains, and where to look for performance leaks.

A second important tool (rather, set of tools) for making my system model more effective was sussing out where in the system making a change would be the most effective, beneficial, and lasting. This is not an easy task. Almost as a rule, the important location wasn’t the one making the most noise or where the fires were being fought. Even so, this hardly narrows the list of possible choices.

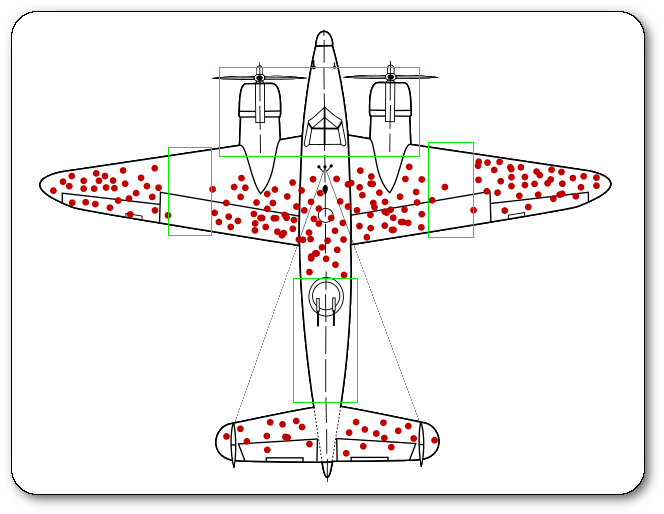

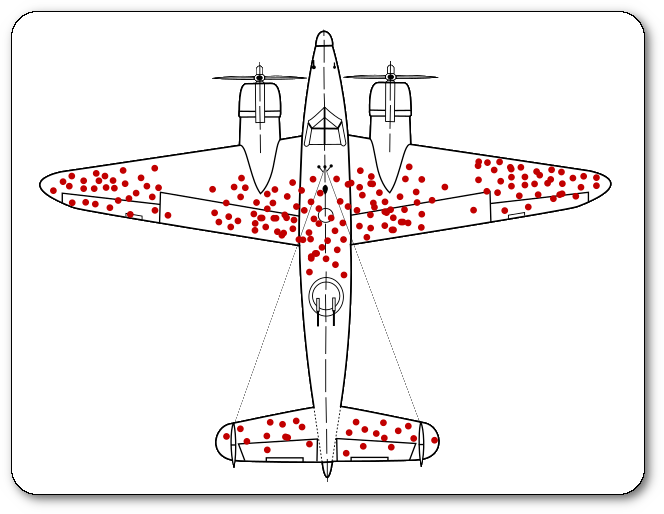

The primary skill to develop with this effort is the ability to find what’s hidden, to find the signal buried in all the noise or see past the flames and smoke and find what’s fueling the flames. My model for developing this skill is based on the work of Abraham Wald. Working for the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University during World War II, Wald was tasked with examining the distribution of damage to bombers returning from missions and recommend ways to minimize the losses. Figure 1 illustrates what such a distribution analysis might show.

The answer to how to build aircraft that would withstand more damage was counter intuitive. It wasn’t found by looking at all the places that were damaged, rather by looking at where the returning aircraft weren’t damaged (Figure 2.) It was inferred that the aircraft that didn’t return had been damaged in the places the returning aircraft weren’t damaged, that is, the engines and cockpit areas. The solution was to add additional armor to those areas and thus increase aircraft and crew survivability. (NB: In cognitive bias terms, focusing on how returning aircraft were damaged is known as survivorship bias.)

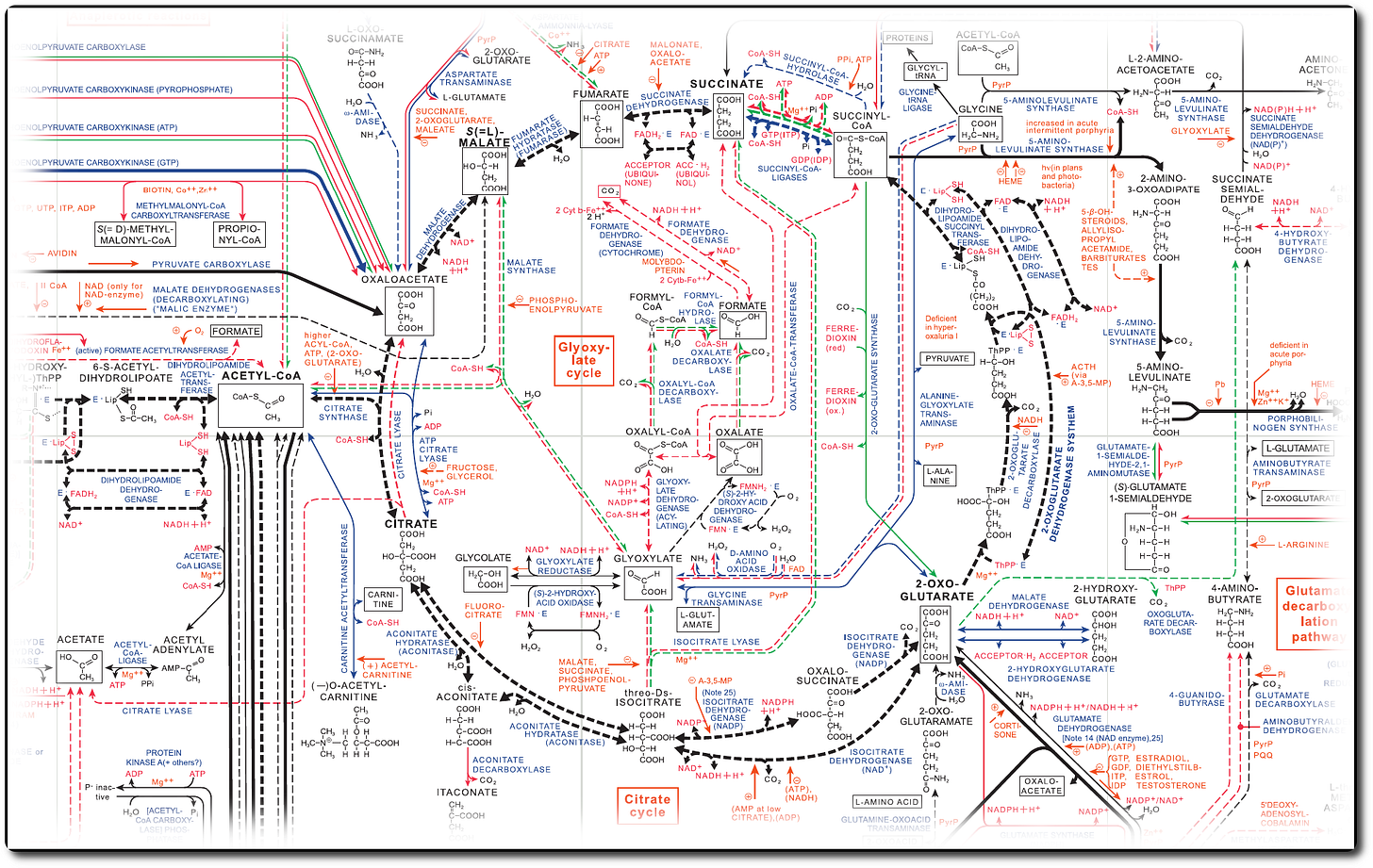

When thinking about personal health, these same principles can be applied in the other direction. The advantage is there are orders of magnitude better empirical evidence supporting how the processes work and how they interact with other parts of the system. In the case of how energy flowed within a software development process and the agents, the physical health counterpart would be how our bodies partition the fuel we consume - that is, the metabolic processes that keep our heart pumping, our muscles working, our brain functioning and millions of other biochemical activities that roll up to “being alive.”

With the WWII bombers, the analysts back at home knew what caused aircraft to fail to return from missions - explosions that sent chunks of metal flying in all directions - they didn’t know how it was affecting the aircraft until Wald did his work. Unlike the WWII bombers, we have mountains of data on how people have died as a result of various metabolic ailments but not much information about how the damage that lead to their death actually occurred. We know a mind-boggling level of detail about what makes a living organism alive, but that pales in comparison to what we don’t know...yet.

Health is a moving target. The wise work with what they have to make the best choices possible, continually scan for better information, and adjust their strategy.

The Noise and Smoke of Metabolic Disease

As complex as my inquiry into cardiac health has been, it seems relatively straightforward when compared to understanding what’s driving the metabolic issues I’m experiencing. I find the principal challenge is the lack of a definitive definition on what constitutes metabolic disease. Obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease all qualify as metabolic diseases. Similarly, the causes are multi factor - genetics, lifestyle, and aging along with numerous underlying biochemical pathway abnormalities can each contribute to any one of these diseases.

What does seem definitive is that insulin is the linchpin. When everything is in balance and no buffers in the system have been overloaded, it works great. Elegant, even. However, it has a non-obvious and often counter intuitive system-wide influence. When its levels go wonky the wheels begin to come off the wagon and all manner of poor health seems to follow - heart disease, obesity, fatty liver disease, kidney disease, and a host of other ailments are bundled under “insulin resistance.”

As with metabolic disease, there is no definitive phenotype that defines “insulin resistance” like there is for diseases such as sickle cell anemia or phenylketonuria, where everyone with such a disease presents the same pathophysiology. It has taken me the last six weeks to get a handle on what is known about insulin and its influence when things begin to go sideways metabolically.

Dr. Ralph DeFronzo, a prominent diabetes researcher, describes2 3 eight key physiological defects, which he calls the “Ominous Octet,” that fit under the insulin resistance umbrella. Each contribute to the resulting cascade of health issues that follow, most notable type 2 diabetes. The organs involved with the Ominous Octet include the pancreas, muscle cells, the liver, fat cells, the gastrointestinal tract, the kidneys and the brain. Each organ manifests insulin resistance in a different way.

The task for any of us trying to find a solution to our metabolic issues is to work our specific phenotype. Unlike Wald’s bombers from WWII where virtually hundreds of identical aircraft were sent on each mission and damage patterns could be compared between each of them, humans can’t be compared as easily when working to resolve something like “insulin resistance.” We’re each an “aircraft of one.” As best we can, we need to assess just where the damage is occurring, work out the underlying causes, and with the help of medical professionals, determine the best strategy for optimal health.

In Part 10.2, I’ll touch on each of the “Ominous Octet” members as I work toward an approximation of my phenotype.

Disclaimer

The author has Bachelor degrees in both biochemistry and cell biology but is not a licensed practitioner of medicine or psychotherapy and nothing presented on this website claims or should be construed to provide medical or psychotherapeutic advice. This series of articles is presented as a personal reflection by the author on work he’s done to improve his health and as such is relevant to the author and no one else. The author makes no recommendations as to any course of action the reader may chose to follow other than to encourage the reader to work closely with qualified health professionals when making healthcare decisions relevant to their personal lives.

<- Health and Well-being - Part 9 - Illness

“Health and Well-being - Part 10.1 - Differences That Make A Difference” last updated on 2025.10.19.

Health and Well-being - Part 10.2 - Resistance is Futile? →

I hope you will return regularly to The Remnant’s Way as I often update posts, particularly Ab Initio, and do not always publish to email posts that are meant to support or serve as reference to existing or future posts.

And please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Doing so supports my writing efforts and grants me the most precious of all resources - dedicated time for writing. And for that, I am deeply grateful. If you prefer, buy me a cup of coffee if there is an article here and there that you enjoyed or found valuable.

Image credit: Roche Biochemical Pathways

Footnotes

James Lyneis and David Ford: System Dynamics Applied to Project Management, System Dynamics Review Volume 23 Number 2/3 Summer/Fall 2007

Attia, P., & DeFronzo, R. (2025, February 24). Insulin resistance masterclass - The full body impact of metabolic dysfunction and prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. https://peterattiamd.com/ralphdefronzo/

DeFronzo, R. A. (2009). From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, 58(4), 773–795. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-9028